ART REVIEW: 'Darkness and Light' at the Portland Art Museum

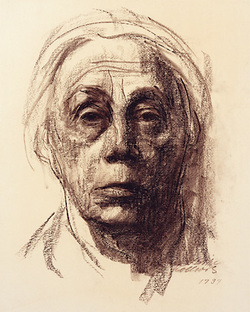

One of the most striking self-portraits at the Portland Art Museum's exhibition on German Expressionism depicts the graphic artist Kathe Kollwitz. Her eyes are haunting, suggesting a rich inner life that is nevertheless scarred by profound sorrow.

It is dated 1924, and reading about Kollwitz elsewhere, one gets an explanation. Ten years earlier, her son became one of the 9 million Germans who were killed in World War I.

War was very much on the minds of the Expressionists, who lived through a tumultuous period of the 20th century. The horror of war was a source of inspiration, if that's the right word for it, and so were social inequality, nightlife, nudism — which emerged in Germany during the late 1800s — and the lives of Africa's indigenous people.

Collectively, these topics permit an essay of the themes that dominate the exhibit: the anxiety of the 20th century's first three decades, and the potential for ecstasy if humanity could find its way out of the dark.

Hence, the name "From Anxiety to Ecstasy: Themes in German Expressionist Prints," which runs through June 11 at the Portland Art Museum.

The exhibit features more than 60 works by some of the most famous Expressionists who flourished from about 1905 to 1933: Kollwitz, Max Beckmann, Ernst Kirchner, Max Pechstein, Otto Mueller and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff.

The Expressionists — they didn't call themselves that; the term has invariably been attributed to art critics and exhibitors — rejected realism in art, the rendering of the world as it actually appears.

Instead, they emphasized the world as they felt it, attempting to bring out the inner reality, the psychological or spiritual qualities, in what they could see.

This attempt at the inner life is evident in the images that greets patrons as they head down the stairs into the Adams Foundation Foyer. The accompanying text informs us that many of the Expressionists used self-portraiture "to document their varying physical and psychological states over time."

Kollwitz did no less than 84. These aren't the visages of self-absorbed artists; they depict souls who had seen something of the world.

What did they see? The dawn of the 20th century was marked by profound social change and the stratification of classes. This phenomenon emerged in Expressionist work in virtually every medium — printmaking, which is the focus of the show, as well as painting, film and literature.

George Grozz captured the ugliness of what he regarded as the self-satisified German bourgoise in "Dinner Party," rendered in graphite with pen and ink. These people, seen by Grozz, are snobs deserving of contempt, hinting vaguely of pigs and rats.

Frans Masereel's "Businessman," a 1920 woodcut, leaves no doubt about where the artist stood. A dark figure looms over the masses, which include, if you look carefully, a skeleton bearing a cross and a soldier.

Kollwitz, for obvious reasons, focused on the psychological toll of war. Perhaps the most stunning is "The Survivors," one of the largest prints in the exhibit. The 1923 lithograph depicts men with bandaged eyes and children, several of whom are gathered in the arms of a woman clearly damaged by life, her eyes blackened by shadow. This and other works by Kollwitz, show the deep empathy she had for human suffering.

The other half of the exhibit highlights what the Expressionists saw as the ideal: human beings in harmony with themselves, with each other and with nature.

Glimpses of the potential for great joy in life were found in a variety of places, at home and abroad, such as the circus and the cabaret. "For the Expressionists," the museum's notes indicate, "the natural movement of dancers, with their open sexuality, symbolized nothing less than liberation."

While some pieces appear to take an almost neutral stance about the liberating qualities of dance, a few take aim at them. In an untitled drypoint, Paul Kleinschmidt seems to go out of his way to highlight the ugliness of three fleshy performers. With noses like snouts, it's as if they were intentionally drawn badly.

Meanwhile, Emil Nolde and Pechstein traveled to German colonies and depicted the native populations of the Palav Islands and New Guinea. There, they found "the freedom, interconnectedness and joy that could restore true values to civilization."

Or at least, some measure of it. The indigenous populations faced their own oppressors, so both native people and colonists appear in the images. One, Nolde's "Slaves," visually reverses the roles, leaving the viewer with a not-so-subtle political statement.

At home, the German nudist colonies that deliberately set out provide a liberating alternative to stifling bourgoise conventions also provided inspiration for Expressionist artists. These nudes, captured outdoors, are unassuming and appear unposed.

Virtually all the pieces, regardless of the medium, are black and white, but the tonal variety is breathtaking. Completely aside from the emotional power of Kollwitz's lithograph "Survivors," for example, the rendering of light and shadow with the blackest of black and the most delicate shades of gray, is a remarkable technical achievement.

In this and other media, the Expressionists elevated printmaking to the level of a major art form for the first time since the 16th century. The artists whose work is on display here were among the best in their field. The 60-some pieces represent a tantalizing glimpse of an important chapter in early 20th century art.

This article was originally published by the News-Register on May 4, 2006.

It is dated 1924, and reading about Kollwitz elsewhere, one gets an explanation. Ten years earlier, her son became one of the 9 million Germans who were killed in World War I.

War was very much on the minds of the Expressionists, who lived through a tumultuous period of the 20th century. The horror of war was a source of inspiration, if that's the right word for it, and so were social inequality, nightlife, nudism — which emerged in Germany during the late 1800s — and the lives of Africa's indigenous people.

Collectively, these topics permit an essay of the themes that dominate the exhibit: the anxiety of the 20th century's first three decades, and the potential for ecstasy if humanity could find its way out of the dark.

Hence, the name "From Anxiety to Ecstasy: Themes in German Expressionist Prints," which runs through June 11 at the Portland Art Museum.

The exhibit features more than 60 works by some of the most famous Expressionists who flourished from about 1905 to 1933: Kollwitz, Max Beckmann, Ernst Kirchner, Max Pechstein, Otto Mueller and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff.

The Expressionists — they didn't call themselves that; the term has invariably been attributed to art critics and exhibitors — rejected realism in art, the rendering of the world as it actually appears.

Instead, they emphasized the world as they felt it, attempting to bring out the inner reality, the psychological or spiritual qualities, in what they could see.

This attempt at the inner life is evident in the images that greets patrons as they head down the stairs into the Adams Foundation Foyer. The accompanying text informs us that many of the Expressionists used self-portraiture "to document their varying physical and psychological states over time."

Kollwitz did no less than 84. These aren't the visages of self-absorbed artists; they depict souls who had seen something of the world.

What did they see? The dawn of the 20th century was marked by profound social change and the stratification of classes. This phenomenon emerged in Expressionist work in virtually every medium — printmaking, which is the focus of the show, as well as painting, film and literature.

George Grozz captured the ugliness of what he regarded as the self-satisified German bourgoise in "Dinner Party," rendered in graphite with pen and ink. These people, seen by Grozz, are snobs deserving of contempt, hinting vaguely of pigs and rats.

Frans Masereel's "Businessman," a 1920 woodcut, leaves no doubt about where the artist stood. A dark figure looms over the masses, which include, if you look carefully, a skeleton bearing a cross and a soldier.

Kollwitz, for obvious reasons, focused on the psychological toll of war. Perhaps the most stunning is "The Survivors," one of the largest prints in the exhibit. The 1923 lithograph depicts men with bandaged eyes and children, several of whom are gathered in the arms of a woman clearly damaged by life, her eyes blackened by shadow. This and other works by Kollwitz, show the deep empathy she had for human suffering.

The other half of the exhibit highlights what the Expressionists saw as the ideal: human beings in harmony with themselves, with each other and with nature.

Glimpses of the potential for great joy in life were found in a variety of places, at home and abroad, such as the circus and the cabaret. "For the Expressionists," the museum's notes indicate, "the natural movement of dancers, with their open sexuality, symbolized nothing less than liberation."

While some pieces appear to take an almost neutral stance about the liberating qualities of dance, a few take aim at them. In an untitled drypoint, Paul Kleinschmidt seems to go out of his way to highlight the ugliness of three fleshy performers. With noses like snouts, it's as if they were intentionally drawn badly.

Meanwhile, Emil Nolde and Pechstein traveled to German colonies and depicted the native populations of the Palav Islands and New Guinea. There, they found "the freedom, interconnectedness and joy that could restore true values to civilization."

Or at least, some measure of it. The indigenous populations faced their own oppressors, so both native people and colonists appear in the images. One, Nolde's "Slaves," visually reverses the roles, leaving the viewer with a not-so-subtle political statement.

At home, the German nudist colonies that deliberately set out provide a liberating alternative to stifling bourgoise conventions also provided inspiration for Expressionist artists. These nudes, captured outdoors, are unassuming and appear unposed.

Virtually all the pieces, regardless of the medium, are black and white, but the tonal variety is breathtaking. Completely aside from the emotional power of Kollwitz's lithograph "Survivors," for example, the rendering of light and shadow with the blackest of black and the most delicate shades of gray, is a remarkable technical achievement.

In this and other media, the Expressionists elevated printmaking to the level of a major art form for the first time since the 16th century. The artists whose work is on display here were among the best in their field. The 60-some pieces represent a tantalizing glimpse of an important chapter in early 20th century art.

This article was originally published by the News-Register on May 4, 2006.