The Lure of a Vast Literary Canvas

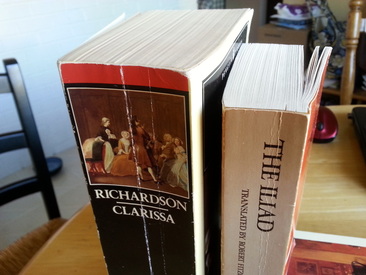

Notwithstanding the truism that quantity does not necessarily equal quality, I confess that with regard to artistic enterprises, I am consistently in awe of and intrigued by sheer jaw-dropping scale: the doorstop book (Richardson’s “Clarissa”), a film that grounds you for three hours or more (Bernardo Bertolucci’s “1900”), or the play that makes drinks afterward impossible because the bars have closed (“The Iceman Cometh”).

It is impossible for me to not at least take note of the particularly vast canvas. I must see the Sistine Chapel before I die, because that’s what I’m talking about.

I don’t know how this happened. It may go back, as most things do, to youth. I remember reading the great epics in high school -- “The Odyssey,” “Beowulf,” etc. and feeling some degree of self-satisfaction that I was reading an epic. Not just a poem, but an epic poem. I recall being only mildly interested in “The Hobbit,” but being awestruck by “The Lord of the Rings.” And while a 12-year-old in 1977 is seduced by the spectacle of “Star Wars,” it wasn't until I was a teenager in 1983 that I was able to appreciate what a deep literary well George Lucas was drawing from. Ewoks were for kids, but the father-son thing was the stuff of Greek mythology. It was epic. In artistic matters, size mattered.

This helps explain the calculus behind “Reading Everest.”

It explains why, when I see a sentence like one at The Millions announcing that filmmaker/novelist John Sayles “has written a freaking huge novel” that I excitedly click over to Amazon to see what the fuss is about -- and, just as importantly, to see how many pages he squeezed out (“A Moment in the Sun,” published by McSweeney’s, comes in at 968 pages).

Other considerations obviously come into play. Lacking the money, and possibly acknowledging at some deeper level that I would never actually read it -- I settled for buying William T. Vollmann’s 752-page abridged version of “Rising Up, Rising Down: Some Thoughts on Violence, Freedom and Urgent Means,” instead of the sprawling 7-volume, 3,298-page edition (also published by McSweeney’s). But understand: If I were to find that in a garage sale for twenty bucks, sold by someone who possibly inherited it and didn’t realize it’s out of print and goes for no less than $300 on Amazon, I doubt that I would be unable to stifle a spontaneous scream of joy.

Actually, the appeal of massive tomes possibly predates those college prep English classes where I first encountered Homer. It may go all the way back to the trips we used to make to my Uncle Ed’s house in Vancouver, Washington when I was a boy and he lived in a big house with a grand view of Vancouver Lake. At the bottom of the stairs, before you arrived in the sprawling basement family room, there was a small area lined with bookshelves, and those shelves included a wondrous sight: all 54 volumes of Britannica’s “Great Books of the Western World, published in 1952. I finally found a set for cheap (relatively so) down in Roseburg a few summes ago, and when I told the clerk I’d buy them and would need help carrying them out to my car, she looked at me like I was a little crazy. Yes, but … will you read them?

In literature, breadth announces the intent of grand purpose. But that's not to say that one cannot produce great work, even epic work, in only a few pages. The 3,951 lines of “Hamlet,” after all, fill only 146 pages in my Folger Library paperback edition and can be savored in an afternoon. I read it regularly, every year or so now.

Being a writer and occasional stage actor, I tend to give artists the benefit of the doubt. No one sets out to make a bad film. No one sets out to write a boring book. It seems to me that if you set out to fill in the neighborhood of 1,000 pages, you have something Very Important to say, and -- if you had the skill and a good editor -- the ability to Say It Well. That's why I trust that Samuel Richardson wasn't simply looking for a way to keep the cash flow up -- "Clarissa" was, after all, first published in installments. The decision to write a 1,500 page novel about a rape is clearly unconcerned with market considerations. No, this was an artistic/intellectual choice.

While I find some of the lengthy exchanges between Clarissa and Lovelace (or Clarissa and her mother) redundant, I do not object to it. It's still working for me, and I see, too, that constructing a tight narrative is not Richardson's intent. The book's design is such that you are literally immersed, insofar as it is possible to accomplish with language, in the consciousness of the characters.

And I've spent a hell of a long time there.

It is impossible for me to not at least take note of the particularly vast canvas. I must see the Sistine Chapel before I die, because that’s what I’m talking about.

I don’t know how this happened. It may go back, as most things do, to youth. I remember reading the great epics in high school -- “The Odyssey,” “Beowulf,” etc. and feeling some degree of self-satisfaction that I was reading an epic. Not just a poem, but an epic poem. I recall being only mildly interested in “The Hobbit,” but being awestruck by “The Lord of the Rings.” And while a 12-year-old in 1977 is seduced by the spectacle of “Star Wars,” it wasn't until I was a teenager in 1983 that I was able to appreciate what a deep literary well George Lucas was drawing from. Ewoks were for kids, but the father-son thing was the stuff of Greek mythology. It was epic. In artistic matters, size mattered.

This helps explain the calculus behind “Reading Everest.”

It explains why, when I see a sentence like one at The Millions announcing that filmmaker/novelist John Sayles “has written a freaking huge novel” that I excitedly click over to Amazon to see what the fuss is about -- and, just as importantly, to see how many pages he squeezed out (“A Moment in the Sun,” published by McSweeney’s, comes in at 968 pages).

Other considerations obviously come into play. Lacking the money, and possibly acknowledging at some deeper level that I would never actually read it -- I settled for buying William T. Vollmann’s 752-page abridged version of “Rising Up, Rising Down: Some Thoughts on Violence, Freedom and Urgent Means,” instead of the sprawling 7-volume, 3,298-page edition (also published by McSweeney’s). But understand: If I were to find that in a garage sale for twenty bucks, sold by someone who possibly inherited it and didn’t realize it’s out of print and goes for no less than $300 on Amazon, I doubt that I would be unable to stifle a spontaneous scream of joy.

Actually, the appeal of massive tomes possibly predates those college prep English classes where I first encountered Homer. It may go all the way back to the trips we used to make to my Uncle Ed’s house in Vancouver, Washington when I was a boy and he lived in a big house with a grand view of Vancouver Lake. At the bottom of the stairs, before you arrived in the sprawling basement family room, there was a small area lined with bookshelves, and those shelves included a wondrous sight: all 54 volumes of Britannica’s “Great Books of the Western World, published in 1952. I finally found a set for cheap (relatively so) down in Roseburg a few summes ago, and when I told the clerk I’d buy them and would need help carrying them out to my car, she looked at me like I was a little crazy. Yes, but … will you read them?

In literature, breadth announces the intent of grand purpose. But that's not to say that one cannot produce great work, even epic work, in only a few pages. The 3,951 lines of “Hamlet,” after all, fill only 146 pages in my Folger Library paperback edition and can be savored in an afternoon. I read it regularly, every year or so now.

Being a writer and occasional stage actor, I tend to give artists the benefit of the doubt. No one sets out to make a bad film. No one sets out to write a boring book. It seems to me that if you set out to fill in the neighborhood of 1,000 pages, you have something Very Important to say, and -- if you had the skill and a good editor -- the ability to Say It Well. That's why I trust that Samuel Richardson wasn't simply looking for a way to keep the cash flow up -- "Clarissa" was, after all, first published in installments. The decision to write a 1,500 page novel about a rape is clearly unconcerned with market considerations. No, this was an artistic/intellectual choice.

While I find some of the lengthy exchanges between Clarissa and Lovelace (or Clarissa and her mother) redundant, I do not object to it. It's still working for me, and I see, too, that constructing a tight narrative is not Richardson's intent. The book's design is such that you are literally immersed, insofar as it is possible to accomplish with language, in the consciousness of the characters.

And I've spent a hell of a long time there.