Confessions of a Contributor to the Idiot Culture

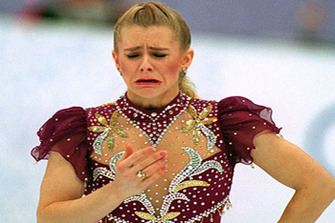

Tonya Harding, as we'll always remember her

Tonya Harding, as we'll always remember her

What is there left to say about Tonya Harding?

This is the question I asked myself Friday night at the Cazadero Inn between flirting sessions with an off-duty waitress as a hundred or more giddy Estacadians huddled in the haze over drinks, waiting for Her Highness to appear so a Hard Copy crew could tape her belting out a tune or two, launching her singing career in Estacada, of all places.

So, what is there to say about Tonya Harding that has not already been said? If there is anything left to say, is it worth saying? If so, will anyone listen? Will they care?

She’s been written up by the best – Jimmy Breslin in Esquire – and interviewed by the worst – Connie Chung at CBS and her equally sleazy colleagues at Current Affair. Tonya compelled The New Yorker to hold up Clackamas County as the white trash capital of the Northwest, and she’s been portrayed as a symbol of working class endurance by Katha Pollitt in The Nation. She’s been the subject of a cheap, made-for-TV movie, and the raw video footage of her honeymoon romp with Jeff Gillooly has been featured prominently in the pages of Penthouse.

I met Tonya a few weeks ago and decided later she’s not someone I’d care to know, if indeed the girl really can be known by anybody who wasn’t in a coma last year, immune from the avalanche of media hype.

Tonya flinched just a bit as I entered the kitchen at the Estacada Fire Department, where she was having coffee with a couple of guys before she started another day of public service, mandated by the Multnomah County DA’s office. You could just see the walls going up, the drawbridge slamming shut. I shudder at the possibility that I might have eventually been granted an official interview so that I could be unleashed at my word processor to write something like this:

She’s not putting out fires yet, but Tonya Harding is doing just about everything else these days at the Estacada Fire Department.

Or maybe …

The hottest thing at the Estacada Fire Department these days is the spunky former Olympic ice skater cleaning up after the guys.

Ten years ago I interviewed actor Larry Linville and later wished I hadn’t. He’s an arrogant ass, not in any way like his Frank Burns, but just as annoying. Watching MASH reruns hasn’t been the same since. Of course, Linville at least contributed his talents to something worthwhile, something of social value and artistic merit. Without having an equally tumultuous interview with Tonya, I feel comfortable in saying that her contribution to society is to illustrate the inclination of the American media the produce – and the public’s willingness to consume – a steady diet of garbage, or junk food news as it’s sometimes called.

Her presence in Estacada, I suppose, is worth noting for the record, but I’m in agreement with the folks who told me they found the Tonya-Estacada connection amusing more than anything else. Call me a snob, call me elitist, call me out of touch, call me anything you like, but I really don’t care about Tonya Harding or Hard Copy, especially on a Friday night when I’ve got a head cold and lungs full of second-hand smoke.

What’s astonishing is that before packing my camera bag and notebook off to this mindless assignment, no fewer than a dozen people confessed to me that what they found really interesting was not the fact that Tonya was singing karaoke at the Caz but that Hard Copy would be there to document the momentous event. By all means, they said, you need to get a picture … not of Tonya, mind you, but of a Hard Copy cameraman.

And people tell me I need to get a life.

So my mission Friday was not to cover Tonya singing in Estacada, but to cover Hard Copy covering Tonya singing in Estacada. After she and her pal Sharon completed a duet – a lovely piece dedicated to the Oklahoma City bombing victims – I chased Tonya down with my Nikon as she was buried by friends congratulating her as if she had just won an Emmy. Hard Copy, intent on capturing the frenzy for all America to see, circled like vultures around a carcass. The cheering crowd, many of whom had been waiting hours over steak and beer for Tonya to show up, finally got the emotional realize they had been waiting for. Meanwhile, yours truly aimed and clicked my Nikon like a madman, even as I asked the Journalism Gods to forgive me for contributing to what Watergate reporter Carl Bernstein aptly calls the idiot culture.

There is nothing more to say about Tonya than what has already been said a thousand times. Who knows what she really is? The only one who knows Tonya is Tonya, and she’s not about to show me, you, Connie Chung, or Hard Copy, no matter how much they pay her. Oh, maybe years from now the world will be treated once again to the horrible visage of a tearful Tonya as she breaks down and admits that yes, , she knew about the Nancy Kerrigan attack from the start. Of course, we’ll all be there with cameras, notebooks and tape recorders, but we’re just players in a freak show of her and our own making. We may be recording the moment, but the thing that haunted me Friday night as I gazed at Tonya through my zoom was the idea that anyone would think moments like these are worth recording in the first place.

This essay originally appeared in The Clackamas County News in May 1995. Tonya hasn't spoken to me since.

This is the question I asked myself Friday night at the Cazadero Inn between flirting sessions with an off-duty waitress as a hundred or more giddy Estacadians huddled in the haze over drinks, waiting for Her Highness to appear so a Hard Copy crew could tape her belting out a tune or two, launching her singing career in Estacada, of all places.

So, what is there to say about Tonya Harding that has not already been said? If there is anything left to say, is it worth saying? If so, will anyone listen? Will they care?

She’s been written up by the best – Jimmy Breslin in Esquire – and interviewed by the worst – Connie Chung at CBS and her equally sleazy colleagues at Current Affair. Tonya compelled The New Yorker to hold up Clackamas County as the white trash capital of the Northwest, and she’s been portrayed as a symbol of working class endurance by Katha Pollitt in The Nation. She’s been the subject of a cheap, made-for-TV movie, and the raw video footage of her honeymoon romp with Jeff Gillooly has been featured prominently in the pages of Penthouse.

I met Tonya a few weeks ago and decided later she’s not someone I’d care to know, if indeed the girl really can be known by anybody who wasn’t in a coma last year, immune from the avalanche of media hype.

Tonya flinched just a bit as I entered the kitchen at the Estacada Fire Department, where she was having coffee with a couple of guys before she started another day of public service, mandated by the Multnomah County DA’s office. You could just see the walls going up, the drawbridge slamming shut. I shudder at the possibility that I might have eventually been granted an official interview so that I could be unleashed at my word processor to write something like this:

She’s not putting out fires yet, but Tonya Harding is doing just about everything else these days at the Estacada Fire Department.

Or maybe …

The hottest thing at the Estacada Fire Department these days is the spunky former Olympic ice skater cleaning up after the guys.

Ten years ago I interviewed actor Larry Linville and later wished I hadn’t. He’s an arrogant ass, not in any way like his Frank Burns, but just as annoying. Watching MASH reruns hasn’t been the same since. Of course, Linville at least contributed his talents to something worthwhile, something of social value and artistic merit. Without having an equally tumultuous interview with Tonya, I feel comfortable in saying that her contribution to society is to illustrate the inclination of the American media the produce – and the public’s willingness to consume – a steady diet of garbage, or junk food news as it’s sometimes called.

Her presence in Estacada, I suppose, is worth noting for the record, but I’m in agreement with the folks who told me they found the Tonya-Estacada connection amusing more than anything else. Call me a snob, call me elitist, call me out of touch, call me anything you like, but I really don’t care about Tonya Harding or Hard Copy, especially on a Friday night when I’ve got a head cold and lungs full of second-hand smoke.

What’s astonishing is that before packing my camera bag and notebook off to this mindless assignment, no fewer than a dozen people confessed to me that what they found really interesting was not the fact that Tonya was singing karaoke at the Caz but that Hard Copy would be there to document the momentous event. By all means, they said, you need to get a picture … not of Tonya, mind you, but of a Hard Copy cameraman.

And people tell me I need to get a life.

So my mission Friday was not to cover Tonya singing in Estacada, but to cover Hard Copy covering Tonya singing in Estacada. After she and her pal Sharon completed a duet – a lovely piece dedicated to the Oklahoma City bombing victims – I chased Tonya down with my Nikon as she was buried by friends congratulating her as if she had just won an Emmy. Hard Copy, intent on capturing the frenzy for all America to see, circled like vultures around a carcass. The cheering crowd, many of whom had been waiting hours over steak and beer for Tonya to show up, finally got the emotional realize they had been waiting for. Meanwhile, yours truly aimed and clicked my Nikon like a madman, even as I asked the Journalism Gods to forgive me for contributing to what Watergate reporter Carl Bernstein aptly calls the idiot culture.

There is nothing more to say about Tonya than what has already been said a thousand times. Who knows what she really is? The only one who knows Tonya is Tonya, and she’s not about to show me, you, Connie Chung, or Hard Copy, no matter how much they pay her. Oh, maybe years from now the world will be treated once again to the horrible visage of a tearful Tonya as she breaks down and admits that yes, , she knew about the Nancy Kerrigan attack from the start. Of course, we’ll all be there with cameras, notebooks and tape recorders, but we’re just players in a freak show of her and our own making. We may be recording the moment, but the thing that haunted me Friday night as I gazed at Tonya through my zoom was the idea that anyone would think moments like these are worth recording in the first place.

This essay originally appeared in The Clackamas County News in May 1995. Tonya hasn't spoken to me since.